Europe's GDPR is good, actually.

More people should have nice things. Like more rights to their data.

Hello friends,

Two posts in a week ?! Yes. I’m turning negative emotions into positive outcomes. Hurray for growth.

Today we’re talking GDPR. “Why?” I hear you asking. Because America.

In short, on May 9th 2022 The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), an American private nonprofit research organization, put out a working paper titled “GDPR AND THE LOST GENERATION OF INNOVATIVE APPS”.

Now that’s quite the provocative title. GDPR is bad for innovation. This made me want to investigate further.

The paper’s abstract clarifies:

Using data on 4.1 million apps at the Google Play Store from 2016 to 2019, we document that GDPR induced the exit of about a third of available apps; and in the quarters following implementation, entry of new apps fell by half. We estimate a structural model of demand and entry in the app market. Comparing long-run equilibria with and without GDPR, we find that GDPR reduces consumer surplus and aggregate app usage by about a third. Whatever the privacy benefits of GDPR, they come at substantial costs in foregone innovation.

Link to the full paper : Here if you want to read a 47 page PDF.

In the abstract the authors clarify that they measured a decrease in available apps in the Google Play store after the GDPR measures were adopted by the European Union, as well as a decrease in the use of apps in general.

The authors, therefore, conclude that this means European Innovation suffered under the yoke of the cumbersome GDPR regulations.

I have some opinions about this conclusion, which I’m casually explaining in today’s post.

Confession : I also have a secondary motive. Two of the biggest and most successful writers on Substack signaled their agreement with the findings of this paper. So not only do I get to write about digital privacy, but I also maybe get to start some Internet drama. Everybody wins !

For the record, the two writers in question are :

Matthew Yglesias. Author of Slow Boring on Substack.

Noah Smith. Author of Noahpinion on Substack and bunny enthusiast. He retweeted somebody else so here’s a screenshot.

So, the stage is set. On your marks, get set, smackdown !

The Cookie Opt-in/Opt-out is NOT GDPR, actually.

Honestly, the second paragraph should have been a “What is GDPR?” quick explainer. The Cookie Opt-in, however, is wrongly attributed to GDPR so often (both Matt and the guy Noah retweeted made this specific point in their tweets) that it’s worth starting with a little debunk.

Cookie consent forms exist because of the EU’s ePrivacy Directive (EPD). It’s different from, but very related to GDPR.

To comply with the regulations governing cookies under the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive you must:

Receive users’ consent before you use any cookies except strictly necessary cookies.

Provide accurate and specific information about the data each cookie tracks and its purpose in plain language before consent is received.

Document and store consent received from users.

Allow users to access your service even if they refuse to allow the use of certain cookies

Make it as easy for users to withdraw their consent as it was for them to give their consent in the first place.

You know lads, getting consent is important.

Cookies are bits of data that websites use to remember you. They are not inherently malicious or invasive. You’re better off that a website remembers your language preferences, for instance. Cookies help websites remember that.

You’re not, however, better off if a 3rd party advertiser or data broker is collecting data about what you’re looking at, what you’re searching for (even when you’re not on the website where the cookie was originally added to your browser, by the way) and then selling that data to another party to use for who-knows-what.

The ePrivacy Directive and the Cookie consent forms make it so you can reject the invasive cookies in example number 2, while not touching the cookies in example number 1.

If you find the consent-forms annoying, consider for a moment that it may be a conscious design choice by the website to get you to accept all cookies in spite of their more negative downstream effects. After all, there’s A LOT of money to be made by selling this data.

Pro-tip : You can use a browser extension to get rid of the cookie-consent prompt altogether. There are quite a few that seem to have a lot of users and good reviews. (like this one, for instance).

I confess, however, that I do not use these on my browsers so I’m only using 2nd hand experience.

So that was a quick bit about the Cookie Opt-out forms, which are not really part of GDPR. But what about GDPR, what does it do ?

What is GDPR about, really ?

The General Data Protection Regulation is an EU-wide law that governs EU citizens’ right to privacy, specifically when it comes to data collection and retention by businesses and other organizations. The legislative document is 88 pages long, so naturally I’m going to shorten and simplify things for brevity.

Here are some highlights:

You don’t gather people’s data just for kicks. It needs to serve a purpose.

If I call your restaurant to make a reservation, the restaurant will need my name and number. That’s fine. But it won’t need my home address, since that has nothing to do with the business of having lunch.

You need to inform and get consent (there’s that word again, kids) when gathering personal data. This is subtle, but important. The information belongs to you. If anyone uses your property without consent, there should be legal consequences, right ?

Data security. Again, think of it as borrowing other people’s stuff. You break it, you buy it. If you’re gathering people’s data it needs to be secure, can’t just leave it in an unprotected AWS S3 bucket and hope hackers don’t notice.

Control over the data. Property rights again. The data belongs to me, not the company that’s gathering it. If I want it deleted, they have to comply. If I want a copy of it, they have to comply. If they want to use my data for something else, they have to tell me and - you guessed it - get consent.

Standards and regulations on compliance. I’m putting a lot into this bucket because it’s more about how companies that gather data should conduct themselves. Not really important beyond “it will cost the company some money to be compliant”. HOWEVER, I do want to point out that the less data is gathered and stored, the less complicated the governance becomes and therefore, less expensive.

So, with this in mind. Let’s get back to the study and what it actually says about innovation and GDPR.

What does the paper say.

First, let me start with what it doesn’t say. I’ll quote something one of the authors posted on his Twitter.

Does this mean that GDPR is bad?

No: Answering that question requires a quantification of GDPR’s benefits. Our point is just that, whatever the benefits of GDPR’s pro-privacy provisions, they come at a cost in foregone innovation

The economists who put together this paper did not do a cost/benefit analysis of GDPR as a policy. They make no prescription or judgement on whether it’s tradeoffs are positive. They just seek to quantify the cost of GDPR in terms of “foregone innovation”.

To be fair and balanced, I also need to point out that this is a backpedal on their part. The title of their paper was “GDPR and the lost generation of Innovative Apps”. English is my second language, but I speak it well enough to see what’s being implied in their title.

Well that should wrap it up, right ? They did a little clickbait with the title and put out a 47 page paper where they showed the cost of implementation of GDPR. Easy !

Not so fast.

What our author means here by “foregone innovation” is “innovation that won’t happen because GDPR will have a chilling effect on new apps and businesses”.

The paper uses 2 main measurements to support this claim.

First, upon the introduction of GDPR they saw a large exit of apps from the European Google Play store. Presumably because these apps were not compliant with the regulation.

But wouldn’t the makers of these apps be willing to invest in making them GDPR compliant in order to remain in the app store ?

That would be the case. The profitable apps would make investments, the unprofitable apps would just exit since there’s no point in further beating the dead horse. So in all likelihood, this large exodus of apps from the store were not the ones that people were actually using.

The author himself agrees.

This exit spike is probably good news all around. The exiting apps had very little usage and, on top of that, were not compliant with privacy regulation. An extinction event, but for intrusive creatures.

So far, so good. Users get more privacy at the cost of (admittedly) a large number of not-that-useful apps.

The second measurement is more interesting. From the paper.

A reduction in the volume of app entry could hamper innovation and undermine the availability of new and potentially valuable apps to consumers, particularly if the quality of apps – like many digital products – were unpredictable at the time of entry.

For the most part, digitization has delivered reductions in entry costs, inducing substantial additional entry in a variety of media product categories. GDPR may be like the digitization in reverse. By raising developers’ costs and reducing their revenue, the regulation may have induced exit and may have prevented the entry of a “lost generation” of valuable apps.

So the premise of the second data-point is that GDPR raises costs for developers and it has a chilling effect on new apps. Somewhere out there some kid from Lithuania could have launched the next TikTok, but because of GDPR he now won’t be able to.

Do we know if that’s true, though ?

I have a lot of follow-up questions, but very little in the way of answers. But I’m leaning strongly towards “no f*cking way”.

Here are some lingering questions :

Do apps have an equal chance of being ‘good’?

The Play and App stores are famously filled with junk, cheap knock-off apps. There’s one ‘Candy Crush’ hundreds of knock-offs. Do we know if GDPR will cause fewer ‘good’ apps to be created or fewer cheap apps to be created ?

It’s not unreasonable to assume that motivated developers will be more likely to make the necessary investments than the people looking to make a quick buck of somebody else’s ‘innovation’.

Is the app all that matters ?

The most downloaded apps in the Playstore in Europe are mainly for big-name services like Whatsapp, TikTok, Pintrest etc. The paper looks at pure number of apps, but not at the “meat” behind them. A notepad app is much less meaty than the TikTok our hypothetical Lithuanian wunderkind would have created. They are both counted as ‘one’ app in the study, but they are in no way the same. Big tech products like TikTok or Netflix aren’t built by one person with a dream, but rather go through an incubation process where funding is secured for development and growth. GDPR could conceivably still be a ‘barrier of entry’ for a well funded incubated startup but a much less dramatic one than for a solo developer bootstrapping a calendar app.

Number of apps will decline, but will the overall quality of services decline ?

Users will get fewer apps on aggregate , but if their needs are met, it won’t lead to a decline in the quality of the Play store as far as user needs are concerned. Imagine for a second how many apps just for taking notes can be found in the stores. Would we notice if half of them disappeared ? Would it impact our ability to take notes ?

Oh, and if the author might be worried about the decline in competitiveness on the app store … I have some news for them about Google, Meta and Microsoft.

Why does your app struggle to exist WITHOUT gathering user’s personal data, anyway ?

I can’t help but point out that there is a rather remarkable bootstrapped web-app that has made waves in 2022 and that is the English-speaking-world-famous Wordle. Wordle requires no account, no personal data collection, it was perfectly GDPR compliant with 0$ extra cost and it was so successful that the New York times bought it for an undisclosed 7-figure sum.

Oh, and now that it’s owned by a large company, it’s filled with trackers.

That snide remark aside, seems way more likely that the additional costs incurred by app developers due to GDPR will encourage them to create products that are less invasive. This, dare I say, might be an expected outcome of the legislation ?

Apps = Innovation is just stupid, sorry.

I know this isn’t a question, and I’m almost not sorry for writing it this way. There are 4 academics involved in the publishing of this paper. Folks who’ve forgotten more about economics than I will ever know. Their use of apps as a metric for innovation however, seems … uninspired.

Here’s something from the author on his reasoning :

Apps are “nobody knows anything” products. As with creative products and many others, it is very hard to predict which newly launched apps will eventually find favor with consumers.

In such contexts, society better finds more “winners” (valuable products) – along with a bunch of additional “losers” – when producers are able to take more draws from the innovative urn (i.e. when more new products enter).

Using this perspective in a 2018 paper, Luis Aguiar and I quantified the benefit of a digitization-fueled tripling in new music entry, finding that the welfare benefit is an order of magnitude larger than the standard “long tail” measures.

His argument here hinges on Apps being similar to creative products. The more folks write and sing songs the more likely you are to discover the next Taylor Swift.

I will seriously dissent to the notion that apps are (purely) creative products. TikTok is full of creative individuals, but as for the app itself ? I think the most creative part of TikTok’s interface is that it is close to invisible, to allow the user to experience the videos as cleanly as possible.

Don’t get me wrong, that’s the sign of a designer that did a good job ! But without the content, without the service, the app is worthless.

So number of apps != innovation, sorry.

But how can we measure innovation? Most likely there isn’t a single metric.

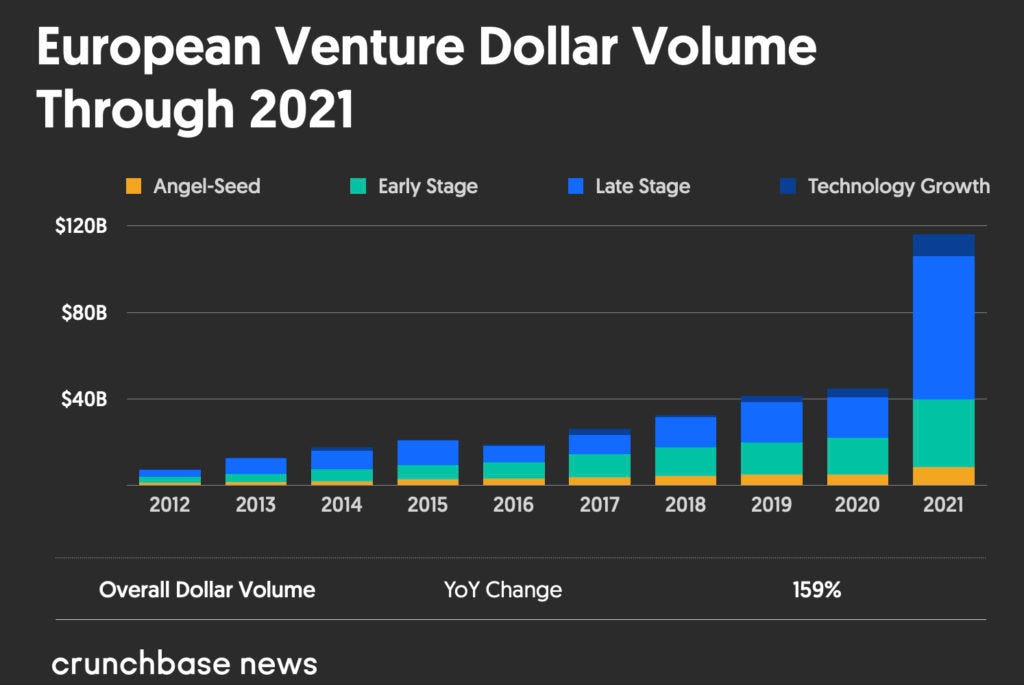

Here’s my take, not so much to prove the existence of innovation, but to disprove it’s absence. With a nice graph from CrunchBase.

Investment into European start-ups has been growing steadily over the last few years (2021 is an outlier until proven otherwise).

As far as European VCs are concerned, GDPR is either not a problem, or not a problem to worry about.

Closing thoughts

I am in favor of GDPR, but my support for it isn’t dogmatic. I support it because we’re better off with this protection than without it. If the costs become too great, I’ll be happy to support making changes.

GDPR has a cost in terms of absolute economic freedom for those running businesses that deal with personal data, there’s no doubt in my mind. This paper does not show this cost. It uses some questionable assumptions about the importance of apps (like it’s 2009 or something) and a clickbait title to get anti-EU and folks with Libertarian leanings to bite.

And here, I go back to my second motivation for writing this post. The two writers I cited at the start …

So to Noah and Matt,

Thanks for reading my Substack, you guys should subscribe !

I really wish I could give two American liberals such as yourselves a good, pointed example about why personal privacy is important.

I’ll let you know if I think of something.

Stay safe out there !

CCS

Funny enough, we had to explain this exact thing to a dev team last month — ended up writing a guide just to help ourselves keep it straight. Happy to share if you’re curious.